Written by Diana Dalton

Edited by Josh Strange

Posters. Chants. Marches. T-shirts. Sit ins. Walk outs. Violence. Division. Throughout the history of the modern university, student protest has been a constant presence. In America, there lies a rich history of student protests ending in triumph, tragedy, and bitter stalemate. Because protest in general frequently tackles issues of culture, the histories of American protest and art culture and inextricably entwined, as art of all forms has been an inspiration to changemakers spanning generations.

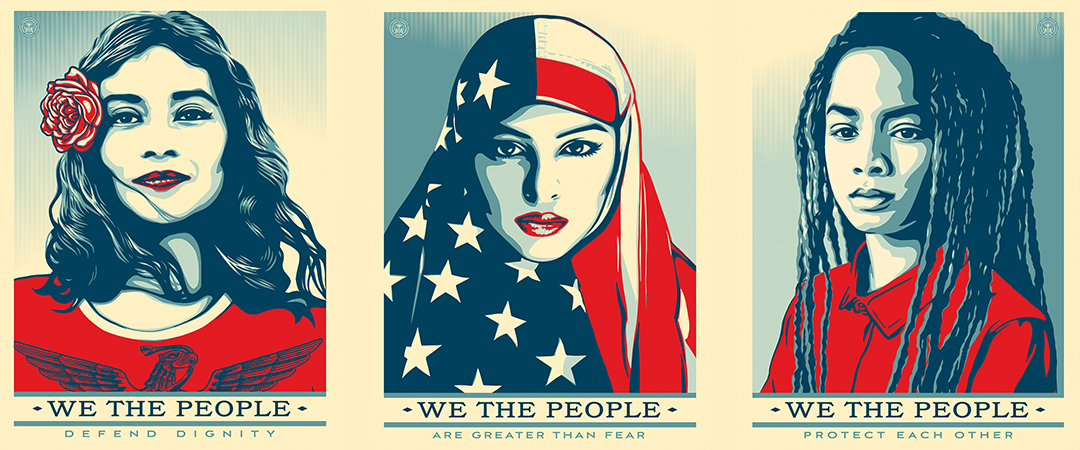

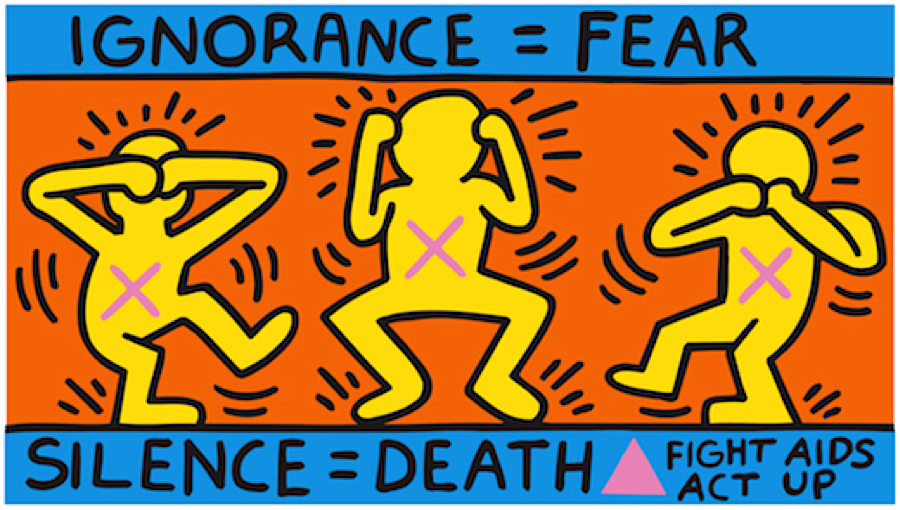

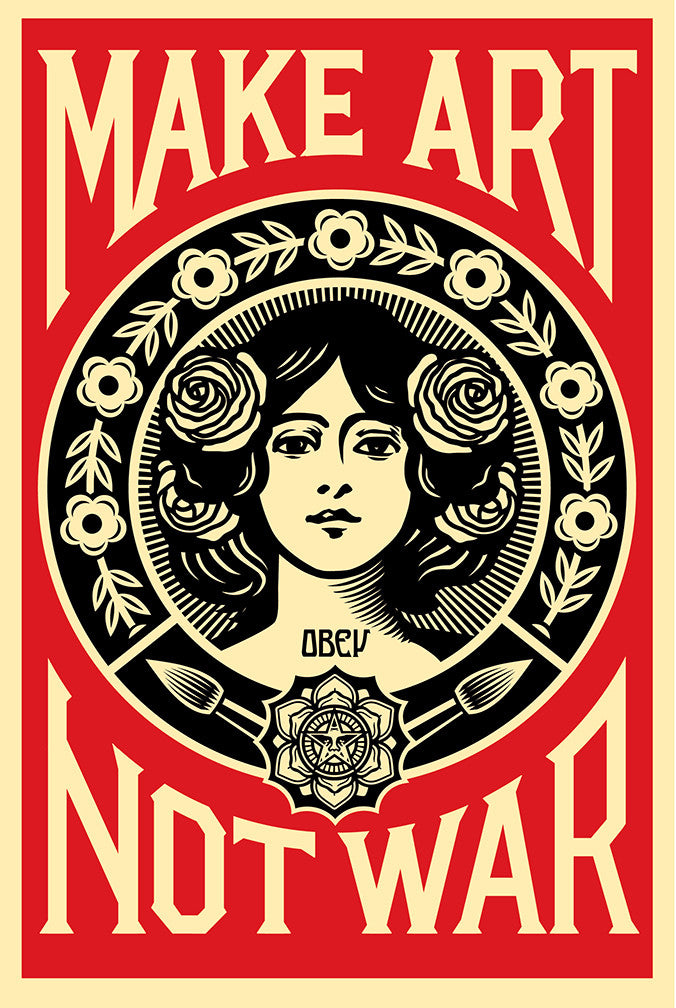

Contemporary protest has long utilized art as a means to sway emotion and opinion. What comes to mind when you picture the 2016 Women's March, for example? Alongside the iconic images of pink-hatted throngs in D.C., the answer is art in every form. Take Shepard Fairey's "We The People" campaign, a poster series created for the march. You may not recognize Fairey's name, but you probably recognize his work: the street-style portraits of a diverse group of American women boldly hued in red, white, and blue. Keith Haring's provocative pop art played a powerful role in bringing awareness to the American AIDS crisis of the '80s. To this day, Haring's dynamic artworks are canonized as quintessential in the protest art movement. Informal collectives also produce impactful protest and performance art, as seen in the radical takeover of the Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, Virginia in July 2020. The controversial statue was adorned with messages including "No America without Black America", painted with various pro-Black and anti-police messages, and became the site of vigils and sit-ins for days. The collective action was later deemed "the most influential form of American protest art since World War II" by The New York Times. The iconic art the Times was referencing could have been Rosie the Riveter, the glamorized factory-working woman who remains a household name eighty years after the war. Although Rosie's once-undisputed status as a feminist icon has been denounced in recent years, there is no doubt that Rosie was a progressive symbol of female power in the 1940s, one which continues to resonate in popular culture today. Viewed side by side, Rose even shares a steely, determined expression with the women of Fairey's "We The People".

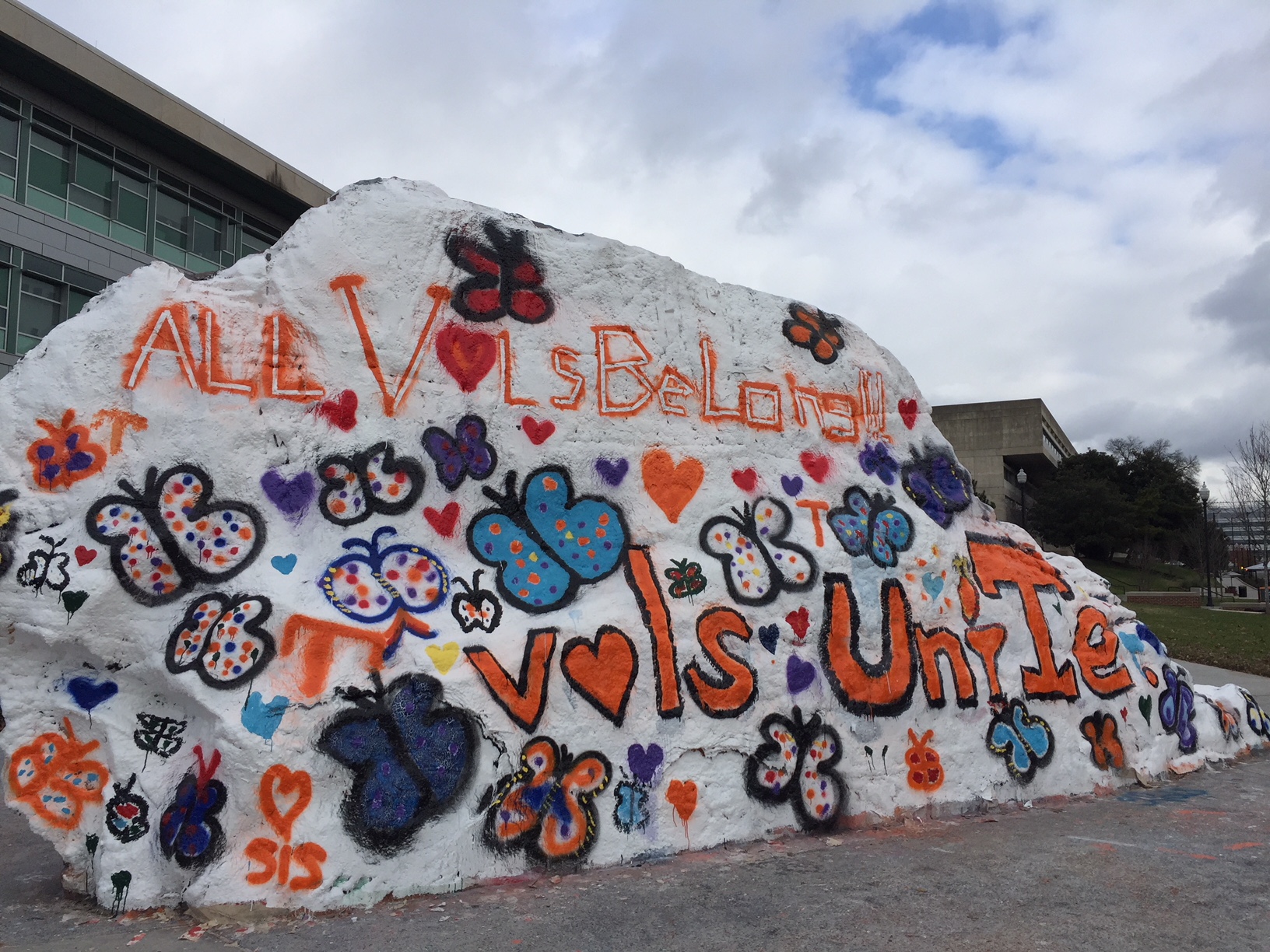

Our campus, like any, is no stranger to cyclical protest art. Chalkings championing social and political causes line sidewalks and Pedestrian Walkway, replaced by the next underfoot gallery with each rain. Lamppost stickers are weathered, scratched away, covered, and installed again. Politically-charged carvings and sharpie scribbles on bathroom stall doors are as common and as inescapable as the next repainting of the Rock.

For over 50 years, the Knox dolomite slab known as "the Rock" has been a unique canvas for student voices at Knoxville's University of Tennessee campus. Installed in 1966 as a symbol of Volunteer strength, the name of the Rock was chosen from a student suggestion reported in The Daily Beacon, and the painting tradition began about 14 years later. A walk past the Rock today will usually offer a club promotion, a holiday or birthday recognition, a meme, or some cacophonous mishmash of all of the above, all lovingly painted amid spray paint fumes and fierce competition for canvas space. Since the tradition of painting the Rock was born around 1980, its 97.5 ton face has worn wedding proposals, a "God Bless America" tribute following the attacks of 9/11, and portraits of revered Volunteers and alums. It has also worn slurs and swastikas. In response to a spate of bigoted messages on the Rock in 2018, the annual "United at the Rock" event began, inviting Vols to slather the Rock in a rainbow of painted handprints as a symbol of unity. The hate speech hasn't stopped, but has become more publicized and villainized since the installation of a 24/7 livestream of the cultural slab in October 2019. The Rock stirs a conversation about free speech, artistic expression, and community accountability. Is it possible for the Rock, owned and monitored by the university, to be a truly liberated canvas of expression? It's certainly a start.

At the time of writing, the Rock's streetside face wears a message promoting Earth Week in a green curlicue font on a sky blue case. Within minutes of watching, it's being repainted again; a small group in matching white T-shirts have converged on it, shaking spray paint cans. The back of the Rock is more of a collage, currently wearing colorful tagging and large blacked out portions.

On our campus and in places where young people congregate across space and time, social values are imprinted on the landscape. Student art is not amateur; we are not junior activists. The cultural exchange between generations is vital to the growth of the ever-elusive "movement", and art on large and small scales keeps the human spirit running, while activism keeps the boundless human capacity in check. Understanding university protest is indispensable to understanding trends of protest and protest art on a broader scale. University protest is a terrarium, incubating and dismantling internal governmental and social practices while looking to the outside world for large-scale environmental cues. The glass is not one-sided; the larger cultural disseminates and adopts the messages carried by young organizers as well. Art has been the pulse of this activism. Art makes the memorability, the outrage, and the introspection of cultural shifts tangible. Art can hold the bleakest and loveliest junctures of the human experience.

Artwork by Shepard Fairey & Keith Haring

Photographs from NBC, UTK News, & UTK Commission for Women