Room 1012

by Kat White

Content Warning: This piece has elements of a murder mystery, mentions of suicide/death, violence, and elements of domestic abuse.

Exhaustion colored the edges of her vision gray and Rue swallowed against the dryness in her mouth with a slight grimace. Mindy hovered behind her at the hotel’s front desk, nervous and unsure, Rue’s own flickering shadow. The large, arching windows in the lobby showed a dark and silent Moorwich outside, nestled between evergreen forests and a silver, spiteful sea. All was quiet and the soft whirring of the golden elevators made Rue’s eyes glance up. Someone was calling the elevator.

“Had a good shift, Rue? Not too busy I hope?” Mindy said, beginning to tie her hair up high into a ponytail as she began to settle her expanse across the front desk: nail polish, books, and study notes began to crawl across the rich wood, and Rue had to avert her eyes. It was late, and the larger battle awaited in her office. Not with Mindy. Rue began to stand up, stretching out a bit, and feeling the ache in her feet from her heels. Mindy wordlessly handed her a bottle of ibuprofen, and Rue flashed her a weak smile.

She has no idea that I’ve been popping this like candy. The familiar weight of the pill slid down her throat, almost in the way a snake swallows an egg, straining against the concave weight of it. It made her feel slimy. Rue didn’t like the fact that she had been taking over-the-counter medications so frequently as of late, but it was the only thing that seemed to help, and Mindy briefly rested her hand on her elbow as she became unsteady. Rue blinked against the bright lights of the lamps that warmed the front desk.

“I hate to do this, Rue, but...this envelope,” Mindy said, and Rue watched her eyes stare past her to the front desk computer, and the thin, lily-white envelope that slept by the keyboard. “Is it overdue?”

Mindy’s voice had dropped to something of a whisper, and Rue gently disentangled her hand from her elbow. “Toss it,” she whispered. “For me. Please.”

Rue could see Mindy’s good nature and her own loyalty to her wrestle behind those glassy, hazel eyes, but the loyalty won out: she could tell by the way her gaze darkened with the burden of it, and Rue knew that she would never see that overdue bill again, until another copy of it arrived in the mail the next time (and, by that point, Mindy would know to just throw it out). Rue flashed her a bright smile, toothy and tired, and dismissed herself from behind the front desk. She never did see that hotel resident come off the elevator.

The walk to her office, adjoined to her gaudy living quarters, was cloaked in shadow and dread, as if the night outside had pressed itself inside and lounged across her armchairs. Harvey will be here any minute now. The familiar sight of a letter from the coroner’s office littered the glazed surface of her desk as she waltzed over to it, slightly disinterested. The wood was imbued with the scent of polyurethane and lemon, and a glossy nail filed to a point slowly scratched the surface, trailing across the gaudy shine until the letter fluttered into a drawer stuffed with torn cream envelopes from the medical examiner’s office. These, at least, she could afford to forget. Her eyes grazed over the envelopes in the drawer that shrouded years’ worth of the Rousure Hotel without a flicker of recognition. It was better that way.

Rue lowered herself into her jewel-toned office chair, pushing back on the desk far enough that it creaked with a protest under her weight. The chain of pearls she wore felt heavy around her neck. Her fingertips brushed against the cool, white surface of them idly, as if she were stroking and rolling little white stars in between her fingers. The vintage shades of her lamp dampened the light in her office enough that the corners of the room were covered in shadow. It was nights like these where the past often came to her in strange ways but, with the Rousure, the hotel wore it as a veil. Rue snorted in amusement as she stared at the linen curtains by the window. My mother never liked curtains. She didn’t like the idea of domesticity.

10:34 pm. She had to squint to read it off the clock, but the time made sense enough. From where her office sat, nestled in the gaudy and ornate folds of the Rousure Hotel, the faint sounds of the hotel breathing and sighing bled through the walls. Most things were quiet. As the hotel proprietor, she was used to this. The delicate waking and sleeping of the hotel was a routine she had mostly perfected, and even Harvey’s arrivals became synchronized with the Rousure’s heartbeat: but, tonight, Rue dreaded it. Her head had begun to pound again, collecting with a heavy pressure behind her forehead, and distant shadows in her office seemed to move and pulsate. She just wanted to get this meeting with him over and done with.

Rue slowly peeled her rings off of her swollen fingers, only looking up to brush a stray piece of platinum blonde hair behind her ear when Harvey knocked, allowing himself into her domain with a flushed look dancing across his pale features. She glanced at the time. 10:36.

“You’re a minute late,” Rue said. With all of her rings off, her hands found the familiar silver of her delicate pen. She needed a drag from it. Anything to lessen her own rough edges, sharpened by the pain and confusion that had begun to hail her. Harvey approached her with downcast eyes, but his gaze was steady.

“Do you do that because it gives you a bit of a dragon quality, like you’re breathing smoke? It’s not good for your health.” He said, lowering himself to the chair opposite to her. Harvey stretched out his long legs, propping them up on the edge of her desk. It was clearly mocking.

“That was just varnished, Harvey.”

He gave her an unimpressed look, and didn’t move.

Rue leaned back in her chair, letting it slide in the dismissive slope of her shoulder as she popped her ankles. “What do you have for me?” And make it quick, please.

“A question.” Harvey’s voice held the soft, diminutive quality of an accent from somewhere European. It took Rue a moment to remember it might be German. “You haven’t read it, have you?”

“The letter? No. Why would I? Don’t you do that for me?”

“This one is different, Rue,” he said, removing his feet so he could lean toward her with insistence. “It is a most unusual case. You’re going to have to comply this time.”

“A most unusual case for a most unusual place,” Rue agreed, aiming Harvey a pointed look. “The Rousure Hotel has a worse reputation than the Cecil. But we have worked together for 15 years, at least, Harvey...and when have I ever been noncompliant?” A sickeningly sweet inflection took to her voice, but the detective--a friend, a touchstone, an adversary--appeared unamused.

Rue felt herself deflate, and she shifted her weight in her chair. “...Let me dissuade you by first saying that I approach this with the best intentions,” she said, picking each word carefully. “However...what is it that you find of note, Harvey, that persuades you to speak to me this late at night?”

His gaze was locked on to hers with an unusual intensity, as if he were searching for deception in the curves of her face. “First of all, you ignored my calls all day. Secondly, you have to ask yourself. Why come to the Rousure to--”

“That’s not entirely unusual,” she interrupted. “People come to the remoteness of the Rousure Forest to vanish all the time. And, besides, the medical examiner--”

“Will try to identify her? That could take weeks: months, even,” Harvey protested. Rue grimaced against the growing edge of defensiveness that sharpened the undertone of his words, and she took another hit. “Didn’t you see what she left behind?”

Rue remembered. Walking the police chief, Todd, up to one of the rooms on the penthouse floor was a walk she had grown accustomed to. Death was as much a resident of the Rousure as the ones he chose to take, and the air had reeked of lavender and soap when they had opened the door. She could almost feel it curling inside her nose. They had found her lying on the crisp, white sheets of the bed like she had fallen asleep, and the room was as if not even a little mouse had stirred during the dark hours of February 12th: nothing looked like it had been touched, and the cold, bright snow that turned the balcony outside white made the room glow with a ghostly luminosity. Soon, Rue imagined, she would forget this one, as well. They always faded from her memory, sooner or later.

“No store tags on her clothes: no brand names on anything she owns, except a Burberry bag,” Harvey said. “That--”

“Now, I remember that Burberry bag,” Rue mused, swiveling around in her chair rather childishly. “That could sell for a pretty penny. You did take it before I entered the room, didn’t you?”

“Yes, but--”

“Perhaps there’s money or some priceless, fairly heirloom in it,” Rue said, rolling the idea over in her mind the way she rolled smoke out of her mouth and off of her tongue. “What do you think? Have you looked in it yet?”

“As evidence. I took it as evidence, Rue,” he snapped, and the venom that came from him slapped her in the face enough to pay attention. She felt a little cautious after taking that misstep, like she had just stepped on the loudest floorboard Harvey had in the well-worn house they had built through these meetings. Looking through the thin veil of vapor that swam in front of her face, it looked like he had swelled up a bit like a pufferfish. Rue knew better than to jab at him further, for a while. He could pop.

“...Look,” he said. “I’m trying to tell you that this is a case with odd, extenuating circumstances that makes the Rousure all but certain to be devoured by the press. Again.”

“What?” Rue startled at that, her momentary spark of guilt gone. “When? How much time do we have?”

“You have sixteen hours,” Harvey said, and there was a cold detachment to his voice that made something inside her chill. His grizzled face was half-shadowed by the dimness of her office, but the part of it that was illuminated by the dirty tinge of the lamp was cold. The sight of that scared Rue more than any death she had seen in the Rousure.

Rue didn’t respond, at first. Sixteen hours? The silence was oppressive. It weighed on her skin like a gown made of stone, and reached beyond her to fill and expand against the cracked windowsill behind her, the creaky floorboards, the velvet armchairs and plastered walls. His eyes bored into her like two burning coals, as if he could burn an answer out of her.

“S-sixteen hours?” She finally said. Her mouth was dry, and she tried to move past the uncomfortable thickness of her own tongue. “That’s, that’s not enough time for us, Harvey, I mean--the guests will want an explanation or added security at the doors, and I--”

“There’s something you’re not telling me.” It fell out of his mouth as a statement rather than a question. She imagined the weight of it crashing through the floorboards. “You know what’s interesting, Rue? There was a two hour gap between Mindy discovering Selene, and you calling me at some ungodly hour of the night. Why was that?”

“....I--”

“Not even a 911 call, Rue,” he pressured.

“We’re behind. Financially,” she finally said, spitting out the phrase like it was glass that had slashed the inside of her mouth. “On everything. We’re getting less and less guests each season. We’re behind on our bills. I mean, Harvey,” she laughed, an almost hysteric note underlying her tone. “Like the Rousure needs another publicized murder! That two hour gap meant nothing!”

“So, what? Did you want to hide the body before I found out?” She wasn’t used to being on the accusing end of Harvey’s theatrics. Even when they had first met, in the police station, he had been gentler than this. “I don’t think you had anything to do with Selene’s death, Rue, but...you didn’t take anything, did you?” he said. Rue found her anger rise against his steady morality, and that familiar bird of panic had taken to whistling inside her ribcage.

“I called you, didn’t I? You know me,” she said. She even sounded weak to her own ears, and Harvey leaned forward, pleading. The way his face stitched together reminded her of an exclamatory I. She only ever really noticed it up and along the bridge of his nose, when his eyebrows furrowed together. Rue tried to appear unmoved by it, but she wanted to talk more to Harvey her friend, than Harvey the police detective. She wanted to tell him that she was sick: that, even if she had stolen in the past, it had been out of desperation, and never for herself: and that she had saved his life, once, and that he could always trust her.

That memory, of blood steaming, tires screeching and metal groaning, seemed to rekindle in his own eyes. Harvey’s frosty demeanor warmed. “You know I’m just trying to keep you safe,” he reassured her, speaking softly. “But it’s difficult when you put yourself in these complicated situations, Rueby. Tell me you didn’t do it.”

Rueby. She pretended to ignore the pet name, and Rue inclined her head toward him. “I did not,” she murmured. “And I would not. I make your life hard enough, Harvey.”

“Oh? You’d consider making it easier, then?” The cold, icy bridge that had formed between them thawed as quickly as it had frozen over, and Rue felt an uncanny feeling of relief wash over her. His voice sounded distant because of it. “Make it even easier, and shut this place down.”

She whipped her head up at that, already opening her mouth up to retaliate.

“Think about it?” His words wavered with the high, sing-song uncertainty of a beg.

She wouldn’t, but Rue inclined her head slightly to humor him. Harvey smiled, nearly leaping out of his chair with triumph at the idea of a Rousure-free Moorwich. It settled on his skin in the same way the tinge from the lamp did, but, this time, it was golden and brighter and without the touch of darkness she had come to expect. It was hope lacquered with fool’s gold. Rue had no intention of giving up the Rousure.

Lying to Harvey was never easy, but Rue had perfected the craft.

It had been carefully sculpted out of the mud of their relationship of 15 odd years, until it was a perfected blade of conciseness that she handled as skillfully as anything. Sleep that night had been uneasy, though. She didn’t like doing it. Without Harvey, Rue had down to nothing that kept her in check: except the Rousure, of course. Except the Rousure.

The Rousure knew her even more intimately than Harvey did, in part because it got to see her stumble and stagger each morning as her sickness grew worse and worse. Rue could feel its dark, lacquered eyes watching her in her moments of weakness, when she either pressed her hands desperately against the countertop in the kitchen to remain steady, or braced herself against the wall as her vision slurred into incomprehensible shapes. Sometimes, she still thought that she could hear her mother’s sharp, dark heels galavanting down the corridors, coiled and black as a scaled whip. The Rousure had thrived under her mother’s smooth, stable hand, but her memory stung and nipped at her heels like a viper that snaked under her feet. She always liked the Rousure better than me. If she could see what I had done to it now...

Rue started her morning in the hotel lobby with its grand, ornate arches and pillars, watching the dawn light filter through the large windows that faced the lake and snow-tipped mountains outside. Her head pounded, but it was a dull ache that felt manageable (for now). This morning light was as silver as dew, casting gray, watery pools of light on the marble floor that rippled and snaked together like twists of fate. Feeling coffee slide down her throat, Rue was reminded of what this glossy hotel lobby really was. It was lacquered in decadence, but she knew she was standing in the stomach of the Rousure: where guests were tugged in deeper, toward the heart and brain and bones, and where the Rousure first got a taste--no, a bite--of whoever it chose next. It was not a nice place, per say, but it was hers, and maybe that was why she stayed. Or maybe it was because it reminded her of her mother (and, maybe, it was because she wanted to prove her wrong).

Rue likened the Rousure to a breathing thing that only she could walk safely in. Not even Harvey knew all of its temperaments and moods, though he had been strolling its halls as long as she had. That was precisely why Rue would be going up to Room 1012: it called to her, and she had to answer.

The key was familiar enough to find in the key box behind the front desk, brassy and unassuming as she turned it between her fingers. The last time this had happened was only two years ago: she had given the key to Room 1012 to a man who she last saw embalmed in the glow of red and blue flashing lights. Pressing it firmly into the palm of her hand, Rue walked down the high-ceiling corridor that flowed toward the elevator lobby like capillaries. The reflection of her teal blazer swam in the gold of the elevator doors, but they peeled open for her like a hand, beckoning her inside. It was comforting. The 10th Floor button lit up with a soft, golden glow, and the familiar momentum of rising higher, higher, and higher still seemed to distract her from what she was about to do.

The Rousure was a demanding thing, and it often pushed Rue to the bounds of what she was willing to do. Today, that took the form of sneaking back into the room Selene had passed in, and finding the things she had hidden and stowed away from the clutches of Harvey and the Moorwich Police Department. That two hour block of time had let her become more familiar with Selene than she had ever wanted to. She wasn’t proud of it, but it had worked before. The walk to the glossy door was familiar. Sliding the key into place, the familiar click of the lock settled across her nerves, and the door creaked open on weary hinges. Rue pushed further inside, instinctually turning on the light. Otherwise, the room was cloaked in shadow.

To continue reading, please go here.

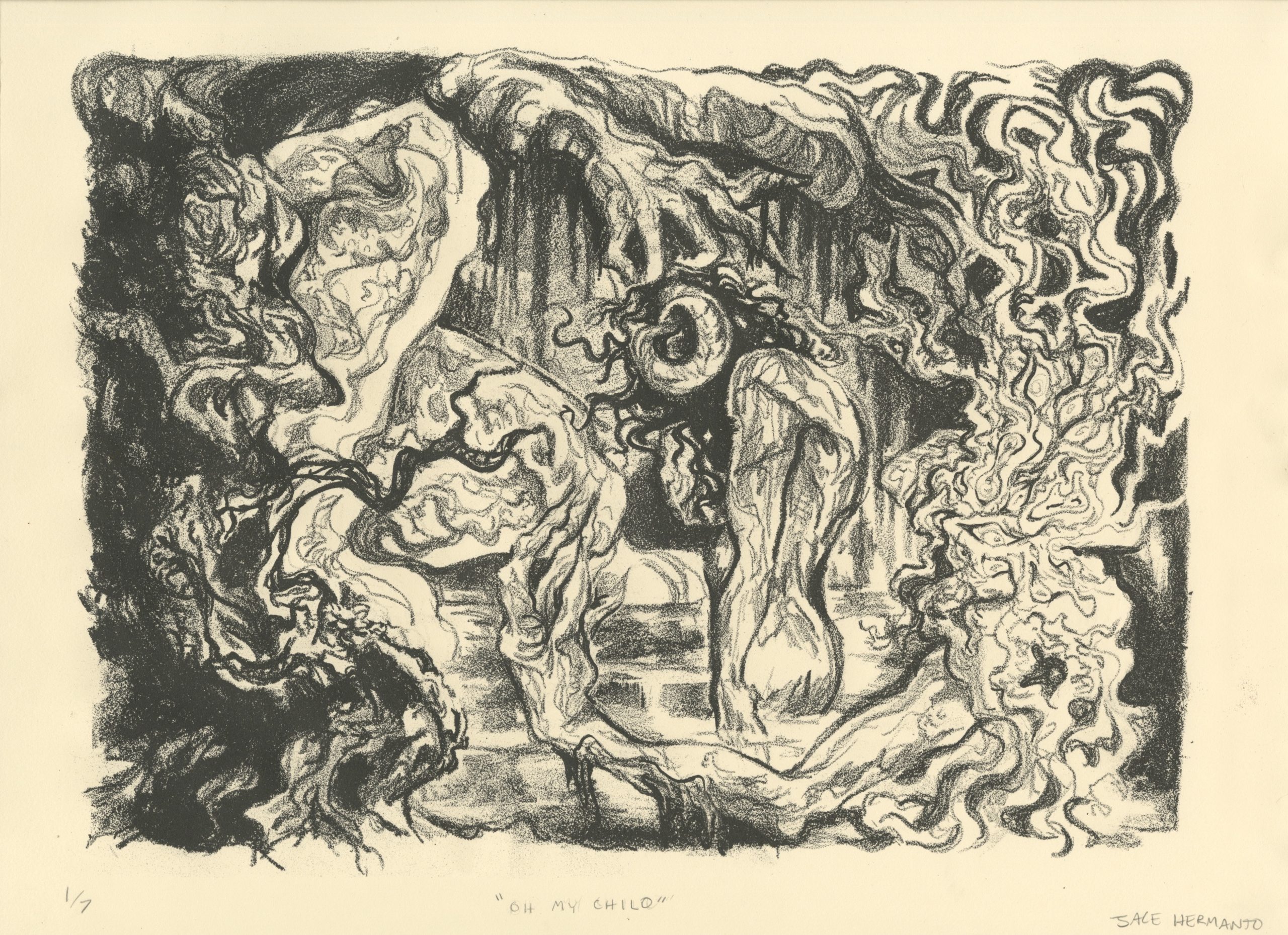

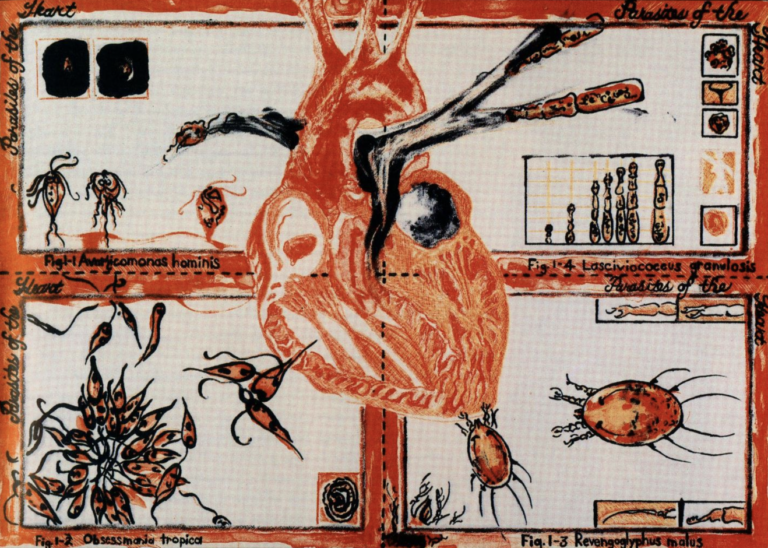

Artwork: "Oh My Child" by Jace Hermanto