By Hannah Malia Kim

Phoenix: Spring 2009

The thing I remember most about my girlhood in Beijing is the hutong neighborhoods. Especially, the way the houses were smushed together so that each shanty looked like a piece of a bigger thing. Almost like a brick and concrete accordion. I used to pretend that I could jump from one house to the next in giant strides, my shoes making thunks on the pavement, careful not to land in the places where the houses touched.

The homes were slanted, with corners worn and steps missing. If you tilted tour head a certain way, they looked like old kitchen wives with heavy bags on their shoulders. The people who lived in the houses like to squat low on the sidewalks, spitting into the street, cursing the weather and the war. The shingles of our own rood would come loose and fall away during thunderstorms, joining the rain in its descent to the earth.

Our shanty was really one half of a home that had been divided down the middle. Mother and I lived on one side and the Ming family lived on the other. Our house alone in the neighborhood still looked new with clean, solid walls of whitewashed concrete. The inside was dark and stank of car piss and garlic. The cat had claimed a section of the living room for himself, shitting and pissing neatly in the corner. I was afraid of it and stayed mostly in the kitchen, looking out the window at the people on their way to the market. My mother liked to watch them too, because they usually turned their heads back once or twice to glance at our house.

“See? They’re noticing our walls.”

My mother’s smile avoided her mouth altogether, leaving it hard and tight. I could tell she was smiling from a certain softening of the eyebrows.

“Our walls are cleaner and more expensive-looking.” I said.

“More Korean,” she said.

Once a week Mother put on some old clothes and scrubbed the walls. Afterwards, her hands would crack and peal from the harshness of the soap. The Mings never scrubbed their walls and our building ended up looking like it has been halfway dipped in bleach. On our trips to the market, Mother would stalk by the Mings’ front windows.

“Chinese women have no sense of cleanliness,” my mother would say.

I would nod, taking a second to work myself up for the next great stride.

The day I found the blue piece of glass was the same day the market vendors stopped obeying my father. It was also the day the light hit my mother in a strange way. It was early. Before the wives with small children could come out, but after the old women had already gone. The relatively empty street made me uncomfortable. Usually, I liked to run my fingers across the textured backs of lychee and Asian pears, hopping from fruit to fruit amongst a purposeful stream of women. Without customers, the vendors looked colorless and out of place. I stayed close to mother, keeping my eyes on the threads that hung up from her shirt sleeve.

“You’re not a toddler anymore.”

She quickened her pace, pushing me slightly until I was left perched between the dumplings and the vegetables. My father hung further back, the shiny buttons on his army uniform peeking through the opening of his jacket. He was standing stiffly, back arched and uncomfortable. The sun was rising at the mouth of the alley, but his figure blocked the light. I squatted where I was, folding my elbows together and resting my head on my hands. Ahead, I could see her approaching our usual vegetable stand. She picked up a few cucumbers and turned to leave.

“That’ll be 60 Yuan.”

“What?”

“60 Yuan. 20 Yuan each.” The vegetable vendor was a tall, skinny man with a pot belly that was puffing up and down like an Adam’s apple. His eyes skipped over to the mouth of the alley, tracing my father’s shadow. His hands were clutching and releasing strands of beans. “Sorry.”

I squinted to make out my mother’s expression, expecting to see the thin, firm line of her lips. But the outline of her body was slightly blurred, tinged with the gray-blue shades of early morning. The light shifted and I noticed my father had left the alley.

“I’m getting the cucumbers to make dinner tonight.”

The softness of her voice made my stomach hurt, and I reached down to scrape my palms against the city road. The rough texture of the pavement felt good. My fingers traced the outlines and ridges and grains of dirt: definite, concrete, and whole.

That’s when it happened. I felt a sharp pain in the bottom of my hand so that, for an awkward minute, I thought the road had bitten me. When I looked down I saw that a piece of glass had cut my palm. A flawless, clear blue piece of glass that was smudged on one corner with my blood. I looked around to see where the glass could have come from, but there was only pavement, and the vendor stands which had wood, cloth, and food but no glass.

My mother was coming quickly towards me, so I put the glass in my pocket. It seemed as good a place as any.

Mt father was an officer in the Japanese army. He stopped every Monday and Wednesday evening for dinner and sometimes on the weekends. He also stopped by for lunch occasionally and to go to the market. He usually came in uniform, the shininess of his buttons and shoes looking too sharp in the dimness of our home. On the evening after I found the blue glass, he arrived early. He sat cross-legged on the floor playing the dominoes with me. When the soup began to boil over on the stove, I ran across the room and stood on my tiptoes to stir it. The broth made sizzling sounds as it hit the burner. The cat was purring.

“Yong-hi, come here,” my father motioned me back to the floor. Mother remained seated in the kitchen, stroking the cat. She had been silent since his arrival.

I sat down. He looked different sitting on the floor. His legs made giant triangles, pulling his army pants taut and exposing his socks. He didn’t usually play games with me. I fingered the blue piece of glass in my pocked, careful to avoid the sharp edges.

“I found a beautiful piece of glass today.”

It took him a moment to focus on my words.

“Where?”

“At the market. I don’t know where it’s from.”

“Probably someone’s eyeglasses.”

I looked at the eyeglasses sitting neatly on his face and tried to picture my piece of glass sitting there. It seemed to be too blue, but I wasn’t sure. I carefully fished it out of my pocket, watching my father. “Do you think it matches?”

He took the eyeglasses sitting neatly on his face and I tried to picture my piece of glass fitting there. It seemed to be too blue, but I wasn’t sure. I carefully fished it out of my pocket, watching my father. “Do you think it matches?”

He took the glass. In my father’s hands, it looked clearer than I had remembered, delivering only the faintest tinge of blue. There was even a slight bend to it, as if it had indeed been a part of an eyeglass lens. He studied it for a moment, turning it over in his hands. Then he looked at me, cupping his chin with his hand, thumb on one side and fingers on the other, in a way I hadn’t seen him do before or since.

“Do you think it matches?” I repeated.

He let his hand drop and shook his head.

“It’s just glass,” he handed it back to me, “is dinner ready yet?”

My mother stood up and dished the soup into bowls. She sometimes made Japanese dishes for the nights my Father ate with us, but tonight our kimchee-jiggae dinner was decidedly Korean. Halfway through the meal, she finally looked at my father, her lips thin.

“I’m sorry there’s no cucumber salad. There was trouble at the market.” My father’s face tightened and he shook his head in response. A few strands of hair, usually combed firmly to the side, fell across his face.

“How are we supposed to eat?” she said.

“I’ll bring you food from the base.”

I ate my kimchee-jiggae down to the very last grain of rice. I decided that I liked Korean food better than Japanese food even without cucumber salad.

“The stupid vendor,” she said.

My father ate his rice slowly, careful to keep his mouth from getting too full. “You should have known. Too many men have already been sent home. I can’t guarantee you anything anymore.”

After dinner, my mother hovered in the living room, her hands drawn up, standing lightly on the balls of her feet. She resembled the cat, muscles taught, ready to spring. My father sat at the kitchen table, his glasses reflecting the light from the fireplace. The lenses looked like two small candles burning.

“Toshio, would you like to come back with me?” My mother gestured toward the bedroom she and I shared.

He took his glasses off and began cleaning them, making sure to get the corners near the nose piece thoroughly.

“No,” he said.

After my father left, I pretended to go to bed. By pretend, I mean I sat in the doorway to the bedroom, half-in and half-out, watching my mother stroke the cat.

The Ming sisters knew that my father was going to leave Chine even before I did, and told me so afterward. They were two years older than me and knew twice as much. Jia and Jie Ming were stringy, identical pole-bean girls whose upper teeth pushed past their lips, so that their mouths hung open in round O shapes. They liked to play outside after they came home from school, tempting me with dangerous yo-yo competitions or loud rounds of piaji- a Chinese version of Pogs.

I’d wait to join them until after my mother went to take her afternoon nap. She’s leave the cat to stand watch by the door, his flat cat-lips threatening to meow an alarm. To get past him, I put one or two anchovies in a small dish opposite side of the kitchen. Eventually, the salt smell would draw him away from his post. I could hear the wet sucking sounds of him eating as I slipped out the door.

“How was the market?” Jia Ming’s mouth stretched across her big teeth and into a smile.

“Did it smell like fish?” Jie said.

“It only smells like fish on Thursdays, dumb girl,” Jia said.

“If I’m dumb you’re dumb,” Jie said.

The sisters fell to the ground giggling, their mouths even rounder than usual. I stood to the side, admiring their synchronization. The glass in my pocket felt heavy, and I wondered what Jia and Jie would think of it. It if would change for them like it had changed for my father. And then I thought that whatever they thought of it, it’d probably be the same thing.

“Yong-hi,” Jia and Jie had finished laughing and were sitting up, looking at me. Their heads were tilted in opposite directions. I couldn’t tell if they had been whispering or not. “Let’s do something dangerous,” Jie said.

“Yes, somewhere far away,” Jia said.

“I can’t go far,” I said. The cat liked to sit at the window and watch me.

“Well we’ll go without you,” Jie said.

I considered showing them the glass again, just to get them to stay. But outside in their yard, standing in front of their dirty walls, I was afraid to take it out.

“Let’s try the abandoned house at the end of the street,” Jia said, “that’s not too far.”

I trailed behind them, purposefully stepping on the gaps between the houses and feeling a little thrilled at my audacity. I thought about mother and whether she was actually sleeping or just sitting quietly in her room, staring at her walls. Either way, I was sure the cat was with her.

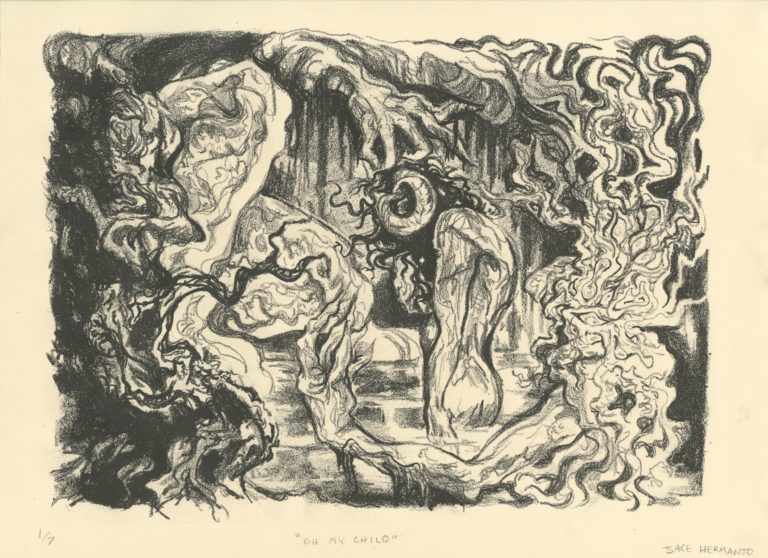

When we arrived at the house I noticed that its walls, like ours, were made of concrete. But large sections of it were missing and broken. Glass littered the yard and the house on either side of the broken walls. There was so much glass that the ground looked like it was covered in clear, sharp snow. Dark, half-enclosed rooms were visible from the street, and I could even see a toilet, its lid gone, its bowl full of brown rain water. A broken bed frame, wood splintered and sticking up at odd angles, and some old children’s toys reminded me that a family had lived there. There was a yo-yo half-buried in the glass. I couldn’t imagine anything significant coming from here. Everything looked like only the outer shells of important things. I felt my hand slip into my pocket and wrap around my blue glass.

“What do you think of all this glass?” Jie said. She walked up to the house and began examining the scattered glass. She bent so low that the tips of her hair trailed across the broken edges.

I took a few steps backward, back toward the houses with people in them, “It’s awful,” Jia said. She took my hand, her fingers firm and filmy with dirt. It was odd to have one hand wrapped around the glass in my pocket and the other hand wrapped around someone else’s. My head cleared and I loosened my group on the glass, transferring some of the pressure onto Jia’s hand. I looked at her, but she wasn’t looking at me. We stayed and explored the house a little longer. On the way home, my hand was smudged with dirt from where Jia held it, and I was careful not to step in the places where the houses touched.

On Saturday my mother decided that it was time to visit the Buddhist temple on the outskirts of the city. She made her announcement while scrubbing the walls of our house. Her fingers, curled and wrinkled over rough cloth, were scrubbing the walls so hard I could see places where her skin was coming off. We packed a lunch and caught the 11:30 bus out of town later that day. I could see the cat in the window as we walked to the station.

The mountains surrounding the Buddhist temple acted like a high rood, enclosing the area. Even though it hadn’t rained in a few days, the ground, air, and wood felt damp and heavy with water. The roods of the temple building had jutted out into the small community, only to be sucked back into the leaves and branches of the mountains. It seemed as if the buildings were only partially available, likely to be consumed entirely by the mountains in the coming decades. I could hear the monks chanting in some private corner, their voices reaching much further here than they would in the city. I wondered what kinds of dwellings the monks lived in, and whether or not they were clean.

The doors of the main worship hall were open, leaving almost the whole side of the building exposed to the dampness of the mountain. But once we went inside, I was surprised to find the room warm and dry. My mother took off her shoes and walked quickly over to the table where hundreds of candles were burning like sprinkles of fire. She lit one and placed it at the corner of the table.

“What’s that for?” I asked.

“Your father,” she said.

Then she went to sit cross-legged in front of the Buddha statue, one pale bare foot facing up toward the ceiling and the other tucked beneath her. I sat behind her careful to imitate her position. We rarely came to the Buddhist temple and my mother never worshiped at home. Temple trips were reserved for the times when mother couldn’t scrub enough dirt off the walls, or when the cat was sick. I just watched her, tracing the graceful outline of her neck, and watching it disappear into the dark depths of her hair. Her lips were relaxed and pink, puffed out slightly. I liked to compare her to the giant golden Buddha, and their identical, erect postures made her look like a smaller, mirror image of the statue. I felt the outline and shape of the blue piece of glass in my pocket. It felt round and smooth, almost fragile, and I realized that the glass could have belonged to my mother. Or at least something she owned, like the glass handle of her yellow, blue and red fan from Korea.

I felt a sense of elation. In the unfamiliar softness of my mother’s mouth, the perfect brokenness of my piece of glass, I could feel the imprint of Jia’s hand in mine. I felt like the abandoned house must have felt before it fell apart. Like my father must have felt when he thought about Japan. It was a scattered feeling-not altogether wholeness, but something like it.

“What’s that?”

I was so surprised to hear my mother break the silence that I didn’t answer her right away.

“A piece of glass I found at the market.”

She stood up in one smooth motion. “Throw it away,” she said, her lips thin,

“You can’t carry around a piece of garbage in your pocket.”

I waited until she was occupied with her shoes before hurrying over to the candle table. I stood the glass up on its side behind my father’s candle. By candlelight the glass looked so blue and thick that it seemed to curve around it, acting as a sort of enclosure. The glass was close to the flame, and I thought the flame might melt a groove in the glass.

That night, my pocket felt empty without the glass, and I cried quietly, hiding my face underneath the blanket. But I fell asleep quickly, and in the morning, it took me a minute to remember why I had been sad the night before.

My father left us the following week. He kissed my mother goodbye and gave me a nod while he put on his shoes. I did not expect to go with him. He was going home.

On the evening after he left, my mother sat in a chair, staring at the wall. I liked to think that she was imagining the giant Buddha statue in front of her. I remember noticing how scarred and broken her hands looked. There were raw spots and cuts where the skin hadn’t healed from the last time she scrubbed the walls.