Written by Josh Strange

Edited by Sadie Kimbrough

It is a societal mainstay that many, if not all, are familiar with seeing in Christian art; curly-haired, handsome men, are shown representing either Jesus himself or other biblical figures. For many, it would be impossible to imagine the religious figures of the Bible as anything other than handsome white men with hair flowing their shoulders and doe-like eyes staring sympathetically into the souls of the believers. What might not be as familiar to many is the origin of this artistic motif and its ancient, homoerotic inspirations that would become inseparable from the way that the people of the world imagine the appearance of Jesus and his disciples. As with many things in our modern society, the origins of these cultural hallmarks can be traced back to the European Renaissance.

Before the Renaissance, religious art in Europe was dominated by two-dimensional illustrations and elaborate calligraphy in large written books known as illuminated manuscripts. Realism, in this time, was not a focus in art and the obsessive attention to anatomical detail that was characteristic of Greco-Roman art had been dead for centuries. It was only until the mid-14th century, with the rediscovery of these ancient texts and artworks that the Renaissance began as an artistic movement.

The Renaissance was a time in which the Classical art of the ancient Greek and Romans reentered popular Western European culture. Many of the nobility and clergy of Europe were amazed at the sophistication and majesty of these art pieces. Naturally, they then sought to emulate the grandeur that they saw before them, so they commissioned the best artists in Europe to take inspiration from the ancient pieces. Gradually, recognizable techniques and motifs of the Ancients began to make appearances in Italian art in the mid-14th century.

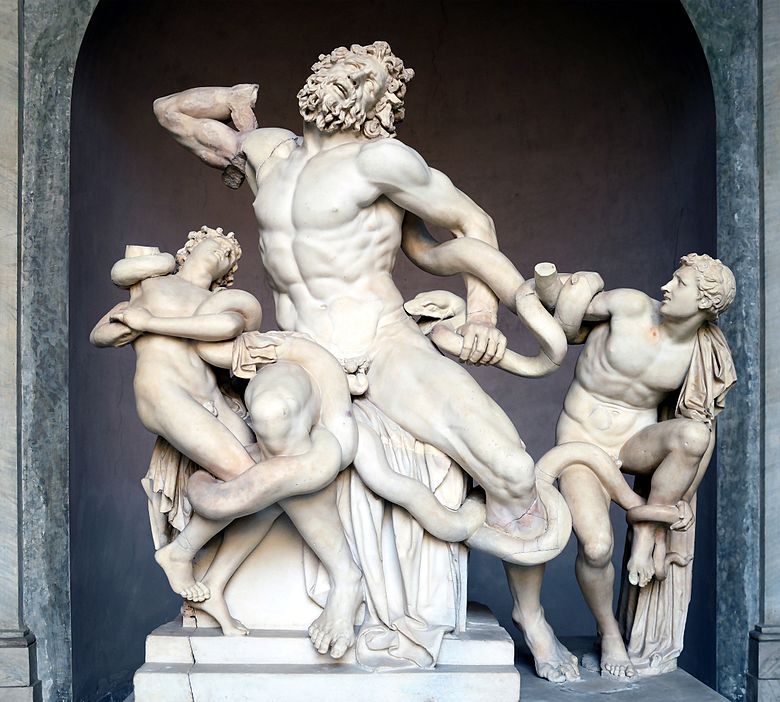

Prized more than any other form among the ancient Greeks and Romans was the nude male body. Magnificent bronze and marble statues were created of men with youthful, adolescent complexions and corded muscles, often depicted in scenes of physical struggle. Notable examples of this include “Laocoön and His Sons” by Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus of Rhodes, and “Discobolus” by Myron.

Reportedly gay artists of the Renaissance, such as Leonardo DaVinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti, were taken with the unabashedly nude art of the ancient Greeks. It was during the lifetimes of these artists that the popular depictions of biblical figures began to more prominently evoke the ancient Greek ideals of male beauty. This fascination with nude figures put many of these artists in direct conflict with the religious authorities of the time, who viewed the prevalence of male genitalia in these commissioned pieces as salacious and sacrilegious.

Pictured above is Leonardo DaVinci’s “St. John the Baptist” in a classic example of this motif. Emerging from the darkness, St. John, in near androgynous form, gazes into the viewer’s eyes with unnerving eroticism. Though clothed, the pose that the saint holds is unquestionably sensual as his lips curve in a soft, yet mischievous smile as though he and the viewer share a secret. His left hand gently caresses his chest, near his heart very delicately like a lover would. In fact, this depiction of St. John is thought to be based on DaVinci’s alleged lover Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, more commonly known as “Salai." Many speculate that the faces of many of DaVinci’s subjects in his paintings are based on Salai’s form.

Another famous artist that had tremendous influence on the depiction of religious figures in the Renaissance was Michelangelo, the genius behind the painted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. To anyone that views the frescoes, the influence of the ancient Greeks will be immediately apparent; countless men in varying forms of undress crowd the walls, all of them possessing almost comically large muscles, their loins either completely nude or draped in dainty, flowing pieces of cloth. In the center of the fresco, framed by these men, is Jesus Christ himself. Depicted too with a hulkish physique and a cascading purple sash, the distinguishing Greek motif of the ideal male body can be seen in Jesus’ form as melding with the artist’s own personal tastes in men. The facial features of Jesus match closely with the descriptions of Michelangelo’s purported lover, Tommaso dei Cavalieri.

On the portion of the walls of the Sistine Chapel known as the “Last Judgement," Michelangelo depicted 20 nude male figures, which he referred to as his “ignudi” (nude in Italian). In several places on the walls, several of these ignudi kiss each other in a display of homosexuality that was incredibly bold when one considers they were painted in the center religious authority in Renaissance Europe. Many religious figures of the day were appalled by Michelangelo’s blatant depictions of male bodies in a place of worship. Biagio da Cesena, a contemporary papal official, said of the piece “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.” So controversial were Michelangelo’s ignudi that loincloths were painted over them by papal decree a generation after the masterpiece was finished.

To this day, the influence of these artists can still be seen in the way that we, as a society, imagine the appearance of Jesus and other biblical figures. When Christian stories are told, in illustrations, television shows, and movies, they are still largely done so with attractive white characters, reminiscent of the homoerotic artistic pieces of the Renaissance.

The impact that these artists had on the portrayal of Jesus for centuries to come cannot be overstated. Michelangelo, Leonardo, and other Renaissance artists were instrumental in constructing the popular Western image of Jesus.