By Zoe Evans

Edited by Collin Green

Nguyen Duc Diem Quynh, also known as Quynh Lam, is a first-year graduate student and Fulbright scholar here at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, studying Painting and Drawing for her MFA. Her work focuses on the ability of historical trauma to decay identity and community. In the Fall 2018 semester, Quynh shared with the Phoenix some of her photos from the Dalat and Hue chapters of her ongoing Mnemonics project.

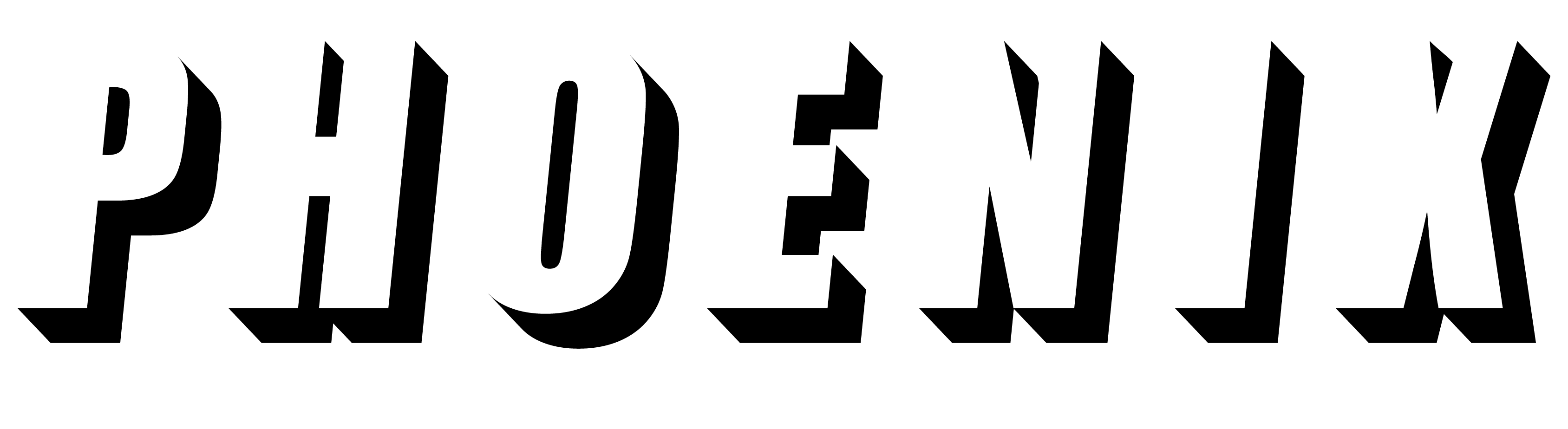

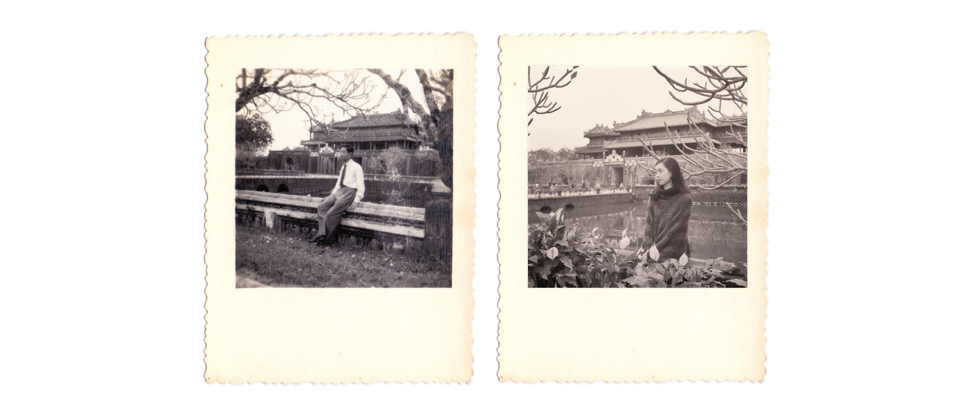

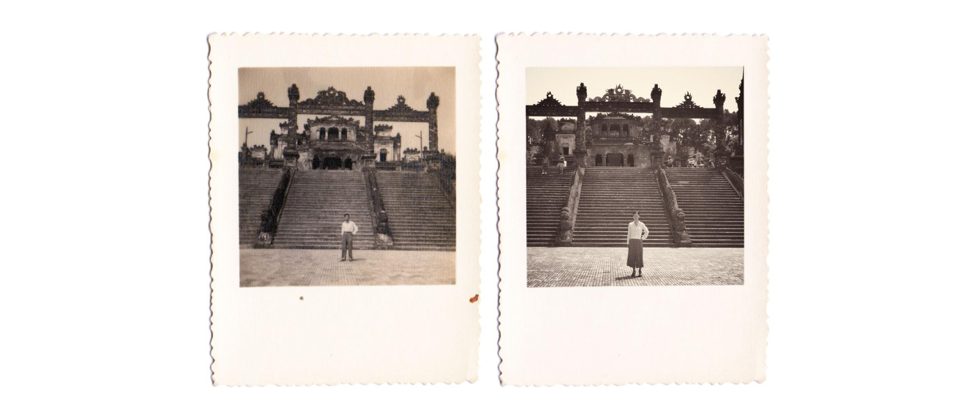

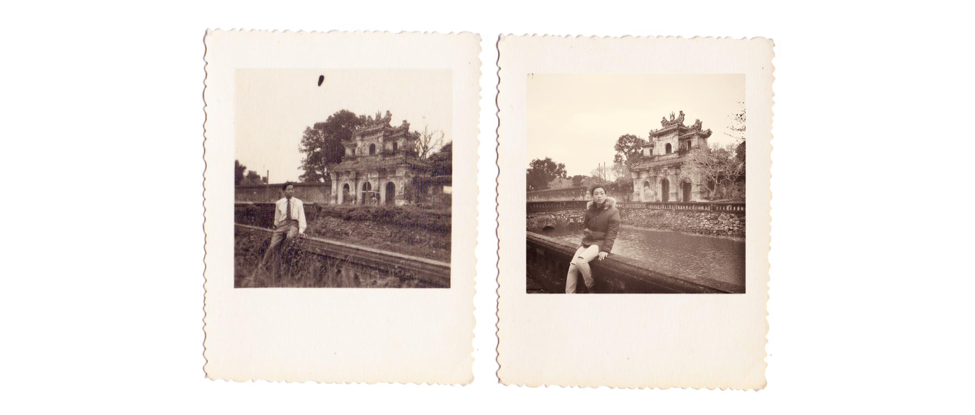

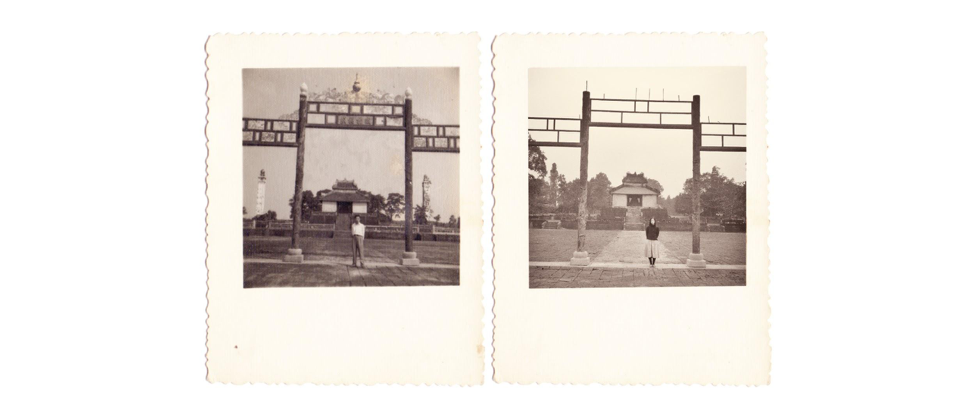

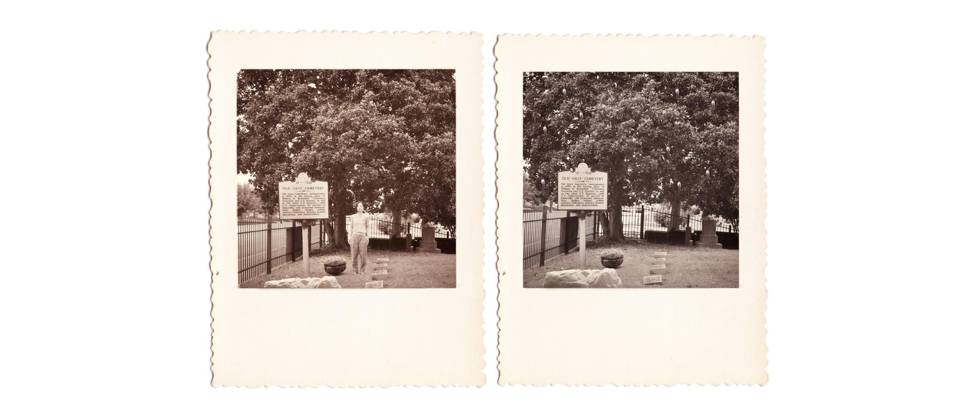

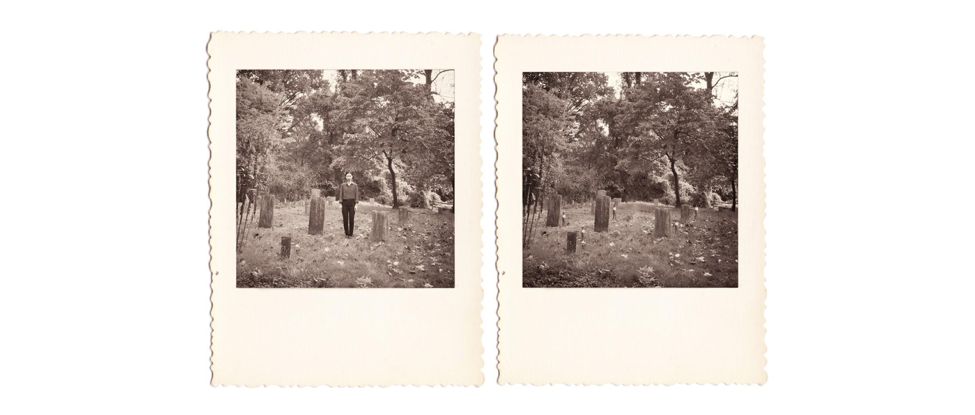

Each of her photos are presented side by side with an almost identical photo. On the left of each pairing, Quynh’s uncle stands in front of Vietnam landmarks, and on the right, Quynh poses herself in her uncle’s position. Some decay over time is visible physically in the representation of the landmarks; seen specifically in Quynh’s image of the Dong Khanh Mausoleum, where bricks have shifted, been uprooted, and whole parts of the arch have gone missing.

In her artist statement on Mnemonics, Quynh discusses her motivation for focusing on and recreating these old photographs:

“When I was a child, I found a treasure chest in my uncle’s room. After many times I persuaded him to open for me to see, it turned out to be filled with old family photos and letters from my relatives. My family moved from the North to the South before the war in 1954, so I myself was born in Saigon. I know nothing about my northern relatives.”

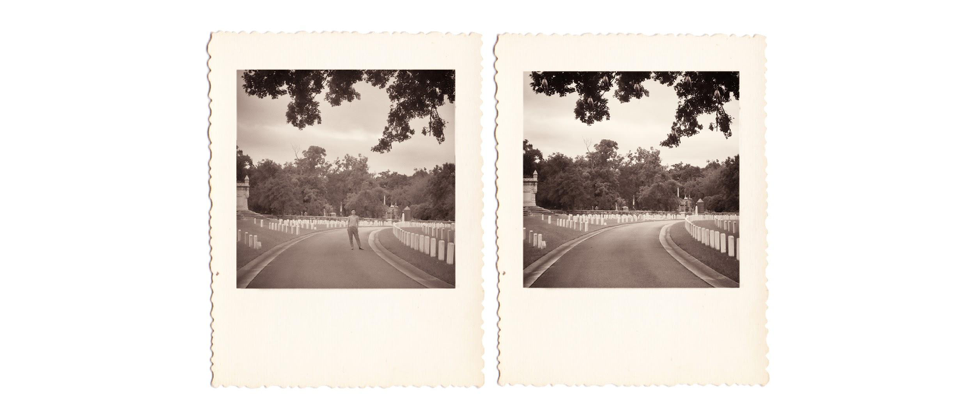

These chapters of Mnemonics, which draw a literal connection between Quynh and her Uncle, all take place in Vietnam. However, Quynh has also developed chapters in Knoxville. In these photos, Quynh stands in cemetaries, specifically locations like Knoxville National Cemetery, which is the resting place for some of the American soldiers who died in the Vietnam War. Here, instead of recreating an older photograph, Quynh composes her own, and then removes herself from the composition and takes another photo with no figurative subject.

“This is another way that I bring my Uncle to the U.S.” she explained. In the same way that Quynh takes her uncle’s place to symbolize her identity in relation to her family and Vietnam as a whole, she lets “ambient air” fill her position in the photographs to suggest that this is where her generation of Vietnamese people lack a connection to their history.

Quynh’s photographs are intended to emphasize decay. Not only the physical decay of the places she visits, and not only of her connection to her own family history, but also of the young Vietnamese people’s willingness to learn about and discuss the country’s history.

“My view of society as a Vietnamese woman is with some kind of trauma, because some of the typical Southern Vietnamese, they don’t really want to remind of the past. The kind of way my parents, they never told me what happened in the past, so I just explore by myself.”

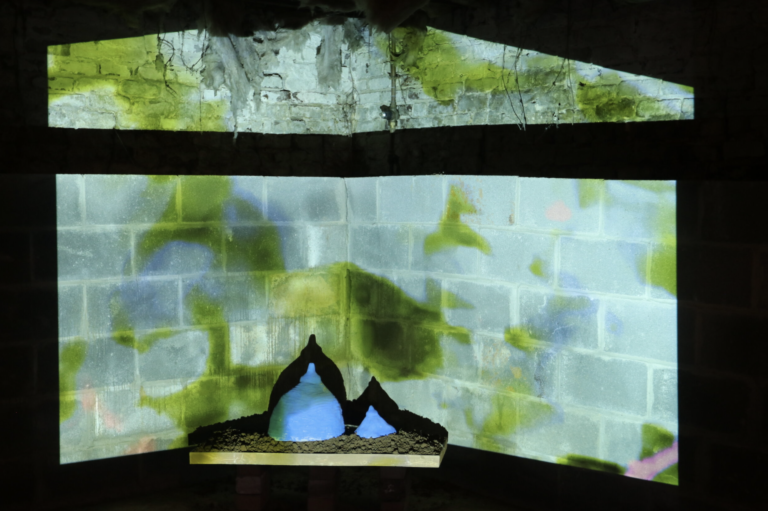

This idea of decay continues through her other projects. In her project Peach from 2015, she expresses her view of women’s oppression in Vietnam. She uses peach peel and fungus as her medium to discuss sexual taboos relating to femininity. In this way, the material itself communicates the theme.

“In 2013 to 2014, I started to create my own pigment from flowers, fruits, leaves—and then in 2015, I was invited to participate into a residency program in Hoa Binh province, North Vietnam, which calls it ‘Eco Art.’

From that residency, I had a chance to meet many international female artists, and we discussed much female body, birthing . . . It reminded me of some stories about women’s function from my colleagues in Architecture firm in Saigon. Every day, I heard a lot of stories from female officers, employees who [had been] pregnant or who used to have experience of giving birth. And all those stories inspired me to create the Birth series. The idea of Peach was developing during the time I was in the residency with Eco Art theme—the Peach series belongs to the Birth collection.”

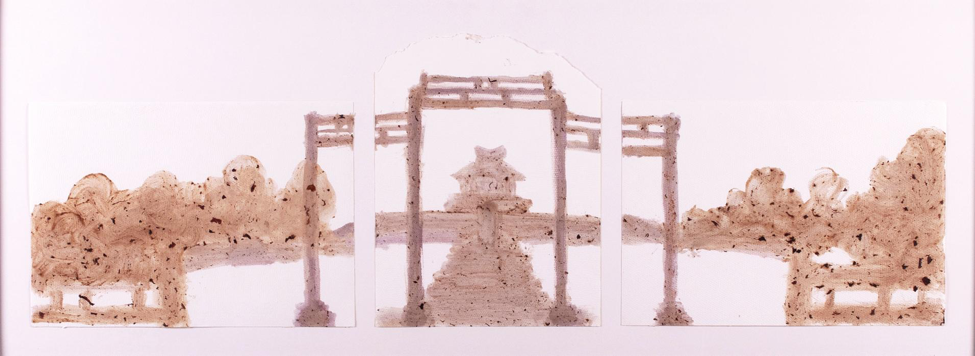

More recently, Quynh finished a series of paintings using various decayed material. These three pieces depict three different Vietnamese mausoleums, using material sourced from three different stages of decomposition. The first, of Thieu Tri Mausoleum, used organic matter that Quynh collected between July and September. The second, of Dong Khanh Mausoleum, used the same from between October and November. The third, of Khai Dinh Mausoleum, was from between November and December. This progression changes the overall impression of the paintings, since the rich colors develop as time goes on. These pieces belong to a collection titled Ephemera.

Quynh had the opportunity to showcase these pieces in an exhibition for winners of the 2019 Art Future Prize in Taiwan. She also won the Special Jury Prize, and was the lone representative artist for Vietnam.

Her art—the pieces discussed previously, and many more—is not only remarkable for its involvement of natural pigments and organic matter, or for it’s striking beauty, but also for its ability to communicate a desperately held individual need for recognition of the past to others, in attempts to mend in the aftermath of historical community-based trauma.

When asked, in a few words, how she might describe her identity, and that of the young Vietnamese people as a whole, Quynh said “I would say the word ‘displaced’ for myself, and I feel a terrible sense of loss towards the young Vietnamese people.”

___

To learn more about Quynh’s success in Taipei this past January, visit this link to UT’s School of Art website: https://art.utk.edu/graduate-student-wins-2019-art-future-prize-in-taiwan/

For more information on Quynh’s past exhibitions and publications, previous works, and history of press, please visit her website: http://quynh-lam.com/