Written by Josh Strange

Edited by Ben Hurst

Lately I have been taking a lot of baths. Feeling the warm water rinse my body as the white porcelain of the tub hugs me tightly is a kind of a therapy. The kind of therapy that has helped ease the stress of being couped up in my house for seemingly endless amounts of time. In the warm embrace of my bathtub, the problems of the outside world are far away, and I feel safe to let my thoughts out to float on the water. The more time that I spend in my bathtub, soaking in the warm therapeutic waters, ruminating over life, the more a Frida Kahlo painting comes to mind. One in which she, like me, ponders the state of her life in a pool of warm, stagnate water.

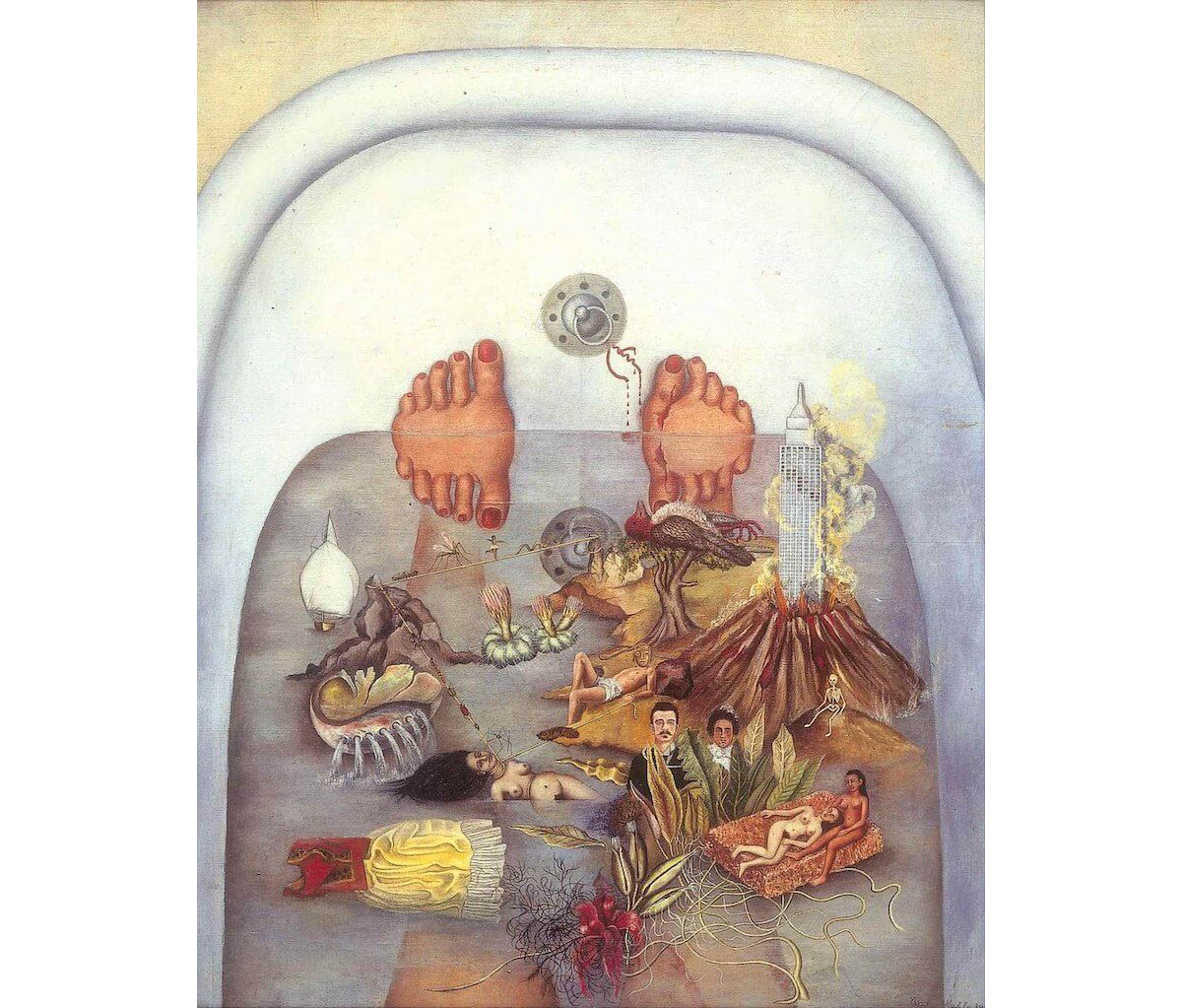

The 1938 oil painting “What the Water Gave Me” offers deeply personal insights into Kahlo’s life at age 31. Unashamed and vulnerable, she invites us to take a bath with her and peer from a first-person perspective into the depths of physical and emotional suffering. Through the aggressive and surreal images floating on the surface of her bath, she paints a disturbing world of pain and frustration—a symbol for her life at the time.

Frida Kahlo’s bath contradicts the typical healing, relaxing bath where a person might escape the stressors of everyday life. Instead of a safe haven, Kahlo’s bath is a fever dream of unpleasant and wretched images: the Empire State Building, amid putrid ribbons of noxious green smoke, spews forth from a volcano, while a man lounges on a beach and strangles a naked, floating woman with string that mosquitoes and spiders are balancing on, crawling towards the soon-to-be-dead woman.

It is uncomfortable for the viewer to witness these grotesque scenes because Kahlo wants it to be uncomfortable. By offering the viewer a first-person point-of-view of a cacophony of terrible sights while at the same time depicting the mundane task of bathing, Kahlo intimately suggests her suffering follows her everywhere in life.

When Kahlo was painting this piece, her relationship with her husband, Diego Rivera, was incredibly tenuous. The two were notoriously quarrelsome with each other, frequently having extramarital affairs. Kahlo created the painting as the couple’s volatility culminated in their divorce a year later, in 1939. Her pain is reflected in the image of a man, Rivera, lounging on a beach carelessly choking a naked woman, Kahlo, from a distance with string.

Notable amongst the other images of the painting are two female lovers on a bed of soil. Kahlo had many affairs with both men and women, and she was not afraid to paint about it. Out of all the other scenes in the painting, which come across as unsettling, the women offer a much more tender depiction of a side of Kahlo’s life. One woman holds the other in her lap, in a soothing, intimate posture. The fondness which Kahlo paints this scene juxtaposes the frenzied pandemonium of the rest of the piece. Indeed, the two lovers offer a kind of respite amidst the symbols of a dying marriage. Kahlo may be presenting an ideal of a relationship that her other romantic partners should strive towards, especially Rivera himself.

These two painted women also appear in Kahlo’s other painting “Two Nudes in a Forest”. While there are many speculations as to who the other female lover in the painting is, some believe it to be famous Mexican Hollywood actress Dolores Del Rio.

In 1938, the pair had been living in Mexico City for four years and had previously lived in the United States. Even when the couple moved to Mexico, they still visited America often due to Rivera’s popularity as a mural painter. However, Kahlo was a staunch member of the Mexican Communist Party and disliked the capitalist consumerism of America. We can see Kahlo’s pain at being forced to America by Rivera in the way the man in the painting pulls, chokes, the woman towards the island with the Empire State Buildings. He pulls her toward the menacing symbol of American culture and away from the beautiful Mexican dress that slowly floats away from her. Kahlo is being tragically ripped from her beloved Mexican culture to the ominous, destructive volcano of America.

Throughout her life, Kahlo suffered physically as well. In 1925, she had gotten into a serious trolley accident that left her unable to become pregnant and with chronic pain for the rest of her life. Her pain is evident in the painting: Kahlo’s left foot is disfigured and oozing blood from a wound caused by a jagged piece of wire in the bathtub. In Kahlo’s time, the expectation that society placed on women still lay primarily in conceiving and raising children. Her inability to bear a child would have caused her tremendous amount of stress as she was unable to perform the task that her patriarchal society placed on her.

In the 1920s and 30s, the male-dominated art world condescended to female artists. The art that women made was not taken seriously and were treated as if it were childlike. In Kahlo’s instance this is also true. While Rivera and Kahlo lived in America, a Detroit newspaper interviewed her and published the article with the headline “Wife of Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art”.

Sadly, this is how Kahlo’s art was treated for most of her life. Her brilliant and raw pieces were reduced by male art critics to the idle paintings of a bored wife by simple, sexist virtue of her proximity to a famous male artist.

Thankfully though, Kahlo did not join the countless ranks of artists whose art was only recognized posthumously. In 1938, when she painted “What the Water Gave Me”, she quickly gained international recognition, holding an exhibition in New York City that same year. The following year, Kahlo would hold another exhibition in Paris and would become the first Mexican artist to be featured in the Louvre after the museum bought one of her paintings. Her powerful paintings have since become famous for their unconventional style and progressive subject matter.

The unbridled expression of her pain as a bisexual woman in a patriarchal-heteronormative world still resonates with millions of people to this day. Since her death in 1954, Kahlo’s status has grown from a renowned artist to an international icon of feminism and the LGBTQ+ movement.

In her painting, “What the Water Gave Me”, Frida Kahlo offers viewers a profoundly intimate experience by expertly painting the intricacies of her life at 31. Kahlo’s artistic brilliance prevails when one engages with her work as she intended it to be. There are few painters, if any, that can compare to Kahlo’s fluency in creating powerful, raw images that cut right to the very soul of a person.